Alopecia Areata (AA) is an autoimmune disorder that causes non-scarring hair loss. Word Alopecia comes from Greek and refers to hair loss or baldness, Areata comes from Latin meaning “occurring in Patches” indicating specific characteristic of hair loss, in most of the cases alopecia areata starts with patchy hair loss areas which can be present anywhere on the body, but most commonly on scalp, beard or eyebrows.

In alopecia areata, the immune system mistakenly attacks hair follicles, causing inflammation. Compared to the most common cause of hair loss, Androgenetic Alopecia, AA has a different hair loss pattern and also disease pathogenesis.

Similarity between the two most common disorders of the hair follicle is different genetic basis, but environmental factors also play a role in the initiation of both conditions. As the second most common nonscarring alopecia, Alopecia areata affects about 160 million people worldwide. Estimated lifetime incidence of the autoimmune disease is 2%. AA can occur at any age, with the highest prevalence in patients between 30 and 49 years. Initially, it was thought that both genders had been equally affected, but recent data suggest that females have a 30% higher prevalence compared to the male population.

Causes of Alopecia Areata

Exact causes of alopecia areata are not fully understood, but there is a link between genetic and environmental factors. Key contributors include genetic predisposition, autoimmune response, and environmental triggers. Strong evidence of genetic association with increased risk for alopecia areata was found by studying a frequent history of affected family members and the occurrence of alopecia areata in identical twins, providing insights into its genetic aspects. Several genome-wide associated studies have identified potential polymorphisms associated with the disease. In addition, alopecia areata shares genetic risk factors with other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and celiac disease. Alopecia areata is associated with many different comorbidities, including atopic diseases, metabolic syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infection, lupus erythematosus, thyroid diseases, and psychiatric diseases. Deficiencies in certain nutrients and vitamins, such as iron, vitamin D, or zinc, may contribute to hair loss and may be associated with alopecia areata.

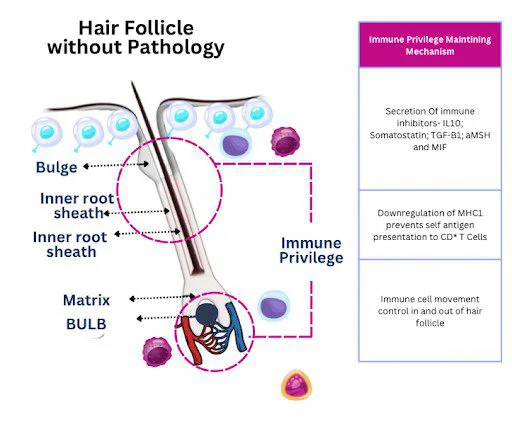

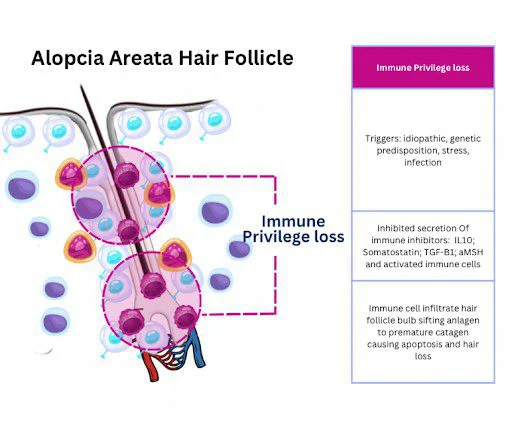

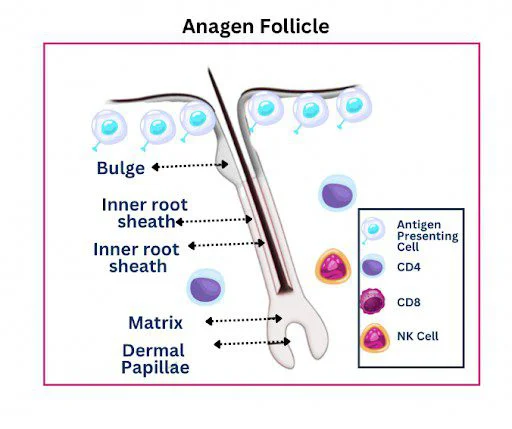

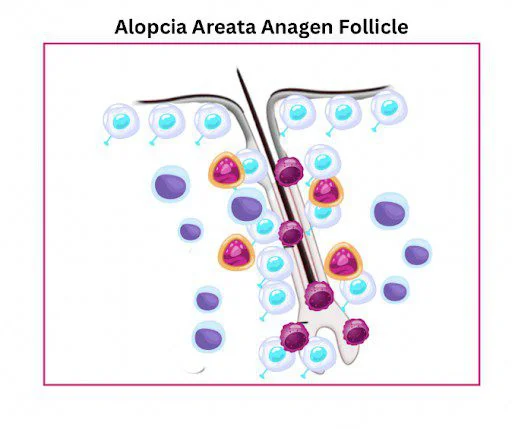

Central to the pathogenesis of alopecia areata is the loss of immune privilege of the hair follicle. In unaffected individuals, hair follicles have an immune privilege that is protective against autoimmunity. In patients with AA, the immune system targets healthy hair follicles, causing inflammation and hair loss. This malfunction of the immune system is thought to be triggered by a breakdown in immune tolerance, leading to the recognition of hair follicle antigens as foreign. Attack of the hair follicle is thought to be directed at autoantigens in the follicle, mediated by disruption of its immune privilege.

Together with genetic predisposition and autoimmune response, environmental factors may affect the initiation process of the disease. Psychological and physical stress often serve as the most common triggers for the initiation of AA. From environmental factors, potential triggers of disease can also be viral infections associated with initial presentation and recurrence of AA, including Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B and C viruses, swine flu. Additionally, vaccines appear to be reported triggers, with many different vaccines including influenza, hepatitis, and coronavirus. Hormonal changes, such as those that occur during pregnancy or menopause, may contribute to the development of alopecia areata.

How is Alopecia Areata diagnosed?

Alopecia areata is diagnosed clinically. Diagnosis typically involves a clinical examination and patient history. Recurrent patchy hair loss and hair regrowth history highly indicates AA. Trichoscopy is used for confirming the diagnosis. Trichoscopy features of AA include the presence of yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, exclamation mark hairs, and short vellus hairs (a sign of early hair regrowth).

Clinical presentation of alopecia areata may include changes in nail plate in 10–30% of cases, Nail changes include pitting and trachyonychia; less commonly reported findings include longitudinal ridging.

Children may have a higher prevalence of nail pitting, which is described as shallow pits in a grid-like distribution, in contrast to the more irregularly distributed shallow pits seen with atopic dermatitis and the deeper, irregular pits of psoriasis.

Skin biopsy is rarely performed by a doctor in cases when clinical findings are inconclusive for conducting differential diagnosis with other causes of hair loss. Skin biopsy may confirm autoimmune inflammation around hair follicles, which can be useful for diagnosing atypical or treatment-resistant cases. Biopsy may be used for histopathology evaluation, in cases when the solitary patch is not presented clinically convincing, or when there is diffuse alopecia and scarring alopecia cannot be excluded clinically. Biopsies should be performed at the edge of a patch and sectioned both horizontally and vertically for optimal interpretation.

Specific blood tests can be used by a doctor for identifying underlying causes or associated autoimmune conditions. While there is no specific blood test to confirm alopecia areata, certain tests can help rule out other forms of hair loss and detect coexisting autoimmune diseases. Tests to exclude potential mimickers of AA include fungal microscopy for tinea capitis and viral serology for syphilis, which can be guided by clinical suspicion.

Early diagnosis of alopecia areata is essential for managing the condition effectively, as prompt intervention may improve treatment outcomes.

Types of Alopecia Areata

There are different alopecia areata types or forms, causing varying amounts of hair loss. As described earlier disease most commonly begins as isolated patchy hair loss.

The three main alopecia areata types are:

Alopecia Areata (Patchy Hair Loss)

Alopecia areata with patchy hair loss causes one or more coin-sized, usually round or oval, patches on the scalp or other places on the body that grow hair. This type may have a risk of progression, converting into either alopecia totalis (hair loss across the entire scalp) or alopecia universalis – hair loss across the entire body, including eyebrows and eyelashes.

Diffuse Alopecia Areata

Diffuse alopecia areata results in sudden and unexpected thinning of the hair all over the scalp. It can be hard to diagnose because it mimics other forms of hair loss, such as telogen effluvium, male or female pattern hair loss.

Ophiasis Alopecia

Ophiasis is a rare form of alopecia areata characterized by the loss of hair in a band shape along the lower sides and back of the head. This form of hair loss gets its name from the Greek word “ophis”, meaning “snake”, because of the apparent similarity to a snake-shaped pattern of the hair loss.

The SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) is a standardized scoring system used to assess the extent of hair loss in patients with alopecia areata (AA). It provides a quantitative measure of scalp involvement, allowing for consistent monitoring of disease progression and treatment response. First proposed by Olsen et al. in 2004, the SALT score divides the scalp into four affected regions: the top (40%), back (24%), and left and right sides (18% each). A score of 0 indicates a full head of hair, while a score of 100 corresponds with complete loss of hair. In practice, the SALT score is quick and easy to perform. However, despite its widespread use, the SALT score does not consider non-scalp factors, which may modulate disease severity, such as facial or body hair involvement.

Treatment of Alopecia Areata

Treatment options for alopecia areata include topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, JAK inhibitors, Minoxidil, and topical immunotherapy. Treatment choice is guided by the severity of hair loss and the patient’s age.

Generally, mild-to-moderate disease is treated with topical agents, and moderate-to-severe disease is treated with systemic therapies. Topical corticosteroids are traditionally used as first-line therapy in children and in adults unable to tolerate intralesional corticosteroids. Intralesional Steroid Injections are administered directly into bald patches to promote hair regrowth. Triamcinolone acetonide is frequently injected at 4–6-week intervals. Long-term use of corticosteroids for alopecia areata (AA) can effectively suppress the immune response and promote hair regrowth, but it also raises concerns about systemic and local side effects. The risks depend on the dose, duration, and route of administration.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors

JAK inhibitors are the newest class of treatments for AA, with oral baricitinib and deuruxolitinib being approved for use in adults with severe AA, and oral Ritlecitinib approved for patients aged 12 years and older with severe alopecia areata.

The JAK family is a group of four intracellular enzymes (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2) involved in immune response. Alopecia areata is driven by the JAK-STAT pathway, which regulates immune system signals. Overactivity in this pathway causes immune cells (T-lymphocytes) to attack hair follicles, leading to hair loss. JAK inhibitors block these signals and prevent further follicle destruction. Pharmacologic inhibition of the JAK enzyme family has been used to treat several immune-mediated diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Generally well tolerated, the most common adverse events associated with JAK inhibitor use can be infection, nausea, transaminitis, lipid panel derangement’s and venous thromboembolic events have also been reported.

Minoxidil

Both topical or Oral Minoxidil can be used as adjuvant therapy for AA to promote hair growth. Thought to be less effective in severe alopecia areata cases, several case studies of treatment-resistant alopecia universalis showed the effectiveness of co-administration of oral minoxidil with a JAK inhibitor, appearing to improve the patient’s SALT score. Cosmetically acceptable regrowth has been also observed in cases of limited patchy alopecia. Adverse effects of topical minoxidil are usually mild, including scalp itching and dermatitis. Hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, fluid retention, tachycardia, and headache are potential adverse effects of oral minoxidil.

As a topical vasodilator commonly used to treat androgenetic alopecia (AGA), clinically proven to be effective in both female and male pattern hair loss cases, its role in alopecia areata (AA) is more supportive than curative. While not FDA-approved specifically for AA, it is often prescribed off-label to promote hair regrowth and maintain regrowth after immunotherapy. Minoxidil has been used in the treatment of various hair loss disorders and appears to demonstrate a dose-response effect.

PRP Therapy

As a part of regenerative medicine PRP (platelet rich plasma) therapy is autologous growth factor therapy which is actively used in the field of hair restoration as a supportive therapy for improved wound healing and implanted hair regeneration after hair transplantation procedure and also as an adjuvant therapy for hair loss for Androgenetic Alopecia, female pattern hair loss, Telogen Effluvium and various stress related hair thinning disorders. PRP procedure is conducted using a patient’s own plasma, which is enriched with the patient’s own growth factors, to stimulate hair follicle repair and promote new hair growth.

While PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) lacks FDA approval for treatment of hair loss disorders or as a specific treatment for hair restoration, still PRP is widely used in clinical practice by hair doctors around the world. FDA has approved PRP for certain medical uses, such as treating chronic wounds for better healing, but its use in hair restoration is considered to be off-label.

According to recent studies, PRP therapy has also gained recognition as a potential adjuvant treatment for alopecia areata (AA). Research, including clinical trials conducted by Trink et al. (2013) and El Taieb et al. (2017), suggests that PRP can effectively encourage hair regrowth, particularly in cases of patchy AA. These studies demonstrated that patients receiving PRP experienced significantly better hair regrowth compared to those treated with a placebo or triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) alone according to guidelines. Furthermore, PRP-treated patients showed improved dermoscopic findings, such as a reduction in dystrophic hairs, indicating healthier hair follicles. The therapeutic effect of PRP is believed to be due to its ability to enhance cell proliferation, reduce cell death, and decrease inflammation around the hair follicles.

Despite these promising outcomes, there is still no universally accepted protocol for preparing or administering PRP in cases of alopecia areata. Treatment effectiveness can vary depending on factors such as the method of plasma preparation, concentration of platelets, and frequency of injections. As a result, further large-scale studies are needed to establish standardized guidelines and confirm PRP’s long-term efficacy in treating alopecia areata.

Vitamin Deficiencies Linked with Alopecia Areata

Certain vitamin and mineral deficiencies may contribute to hair loss and can play a role in alopecia areata (AA) by affecting immune regulation, hair follicle function, and inflammation. While autoimmunity is the primary cause of AA, addressing nutritional gaps may improve hair regrowth and treatment effectiveness.

| Vitamin / Mineral | Role in Hair Health | Impact of Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Regulates immune function & hair follicle cycling | May trigger autoimmune activity; associated with higher AA severity. |

| Vitamin B12 | Supports red blood cell production and DNA synthesis | Linked to hair thinning and weakened follicles. |

| Biotin (B7) | Essential for keratin production | Deficiency may cause brittle hair and increased shedding. |

| Vitamin A | Supports cell growth and sebum production | Both deficiency and excess can cause hair loss. |

| Vitamin E | Acts as an antioxidant, reducing oxidative stress | Low levels may weaken follicles and cause inflammatory damage |

| Folate (B9) | Crucial for DNA repair and cell division | Deficiency may disrupt hair follicle regeneration. |

| Zinc | Immune regulation & hair follicle repair | Deficiency can cause hair thinning and weakened immunity. |

| Iron | Essential for oxygen transport to hair follicles | Low iron (ferritin) levels are linked to hair loss, including AA. |

| Selenium | Supports antioxidant protection | Low levels may increase oxidative stress and trigger autoimmunity. |

Psychological and Social Impact of Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata may have a huge psychological and social impact for patients affected at any age. As described earlier, central to the pathogenesis of alopecia areata is loss of immune privilege of the hair follicle, which can have a connection between both autoimmune and apoptotic pathways, and exposure to stress factors plays a central role in most of the cases associated with increased risk of both initiation or recurrence of the disease.

Alopecia areata can have a negative impact on different aspects of a patient’s everyday life, it may influence socialization, relationships, work, or school performance – all listed negative impacts can affect emotional and mental well-being and may lead to depression and anxiety.

Psychological concerns of affected patients should not be neglected by healthcare individuals. For successful treatment of the disease, it’s vitally important to ensure appropriate support and, importantly, remove stress factors from daily life, taking into account the close relation of AA to emotional stress, influenced by psychological factors as part of its pathophysiology.

Expert Opinion

In our extensive clinical experience managing patients with alopecia areata (AA), psychological stress has frequently emerged as a key triggering factor during the initial consultation. In a significant number of cases, ongoing or chronic stressors have been observed to hinder the progress of AA treatment.

Our observations suggest that the success and sustainability of therapeutic outcomes are often closely linked to the patient’s ability to eliminate or effectively manage psychological stressors in daily life. Emotional and psychological support from family and close social networks, in conjunction with a compassionate and holistic approach from healthcare providers, plays a critical role in achieving favorable and long-lasting results.

It is often necessary for clinicians to look beyond the immediate clinical presentation and explore underlying psychosocial dynamics in order to fully understand the complexity of the condition and tailor the most effective treatment strategy.

FAQs

Is alopecia areata contagious?

No, alopecia areata is an autoimmune condition and cannot be spread to others.

What makes a patient suspect that they may have alopecia areata?

Sudden, round, patchy hair loss – smooth, coin-sized areas of hair loss on the scalp, beard, eyebrows, or other body parts. The patches may develop overnight or within a few days.

Can hair grow back after alopecia areata?

Yes, hair can regrow on its own, but treatment helps to speed up the process.

Can hair be transplanted in case of alopecia areata?

Hair transplantation is generally not recommended as a primary treatment for alopecia areata; however, there can be specific situations where it may be considered.

Is alopecia areata permanent?

In some cases, hair loss may be permanent, but many individuals experience hair regrowth.

Can stress cause alopecia areata?

Stress can trigger or worsen the condition, but it is not the sole cause.

Are there natural remedies for alopecia areata?

Some people find relief with natural treatments like essential oils or dietary changes for hair regrowth, but results vary.

References

Alopecia Areata: The Clinician and Patient Voice –Antonella Tosti MD, Fredric Brandt Endowed Professor, Dr Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, University of Miami, Miami, FL Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, 10/16/23.

“Two Episodes of Simultaneous Identical Alopecia Areata in Identical Twins”

by Nino Lortkipanidze, Abraham Zlotogorski, and Yuval Ramot- International Journal of Trichology in 2016.

Chelidze K, Lipner SR. Nail changes in alopecia areata: an update and review. Int J Dermatol 2018 Jul;57(7):776–783. doi:10.1111/ijd.13866. Epub 2018 Jan 10. PMID:29318582.

Immunology of Alopecia Areata. Żeberkiewicz M, Rudnicka L, Malejczyk J.

Cent Eur J Immunol 2020; 45(3): 325-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.5114/ceji.2020.101264

PMID: 33437185

Alopecia areata: Review of epidemiology, clinical features,

pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology 2018;

10(2): 51-60. Darwin E, Hirt P, Fertig R, Doliner B, Delcanto G, Jimenez J.

Thompson JM, Mirza MA, Park MK, Qureshi AA, Cho E. The role

of micronutrients in alopecia areata: A review. Am J Clin Dermatol

2017; 18(5): 663-79.

Alopecia areata: a review of diagnosis, pathogenesis and the therapeutic

Landscape– Anthony Moussa Laita Bokhari1 and Rodney D Sinclair1,

Sinclair Dermatology, East Melbourne, VIC, Australia

University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Insights into Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review of Prevalence, Pathogenesis, and Psychological Consequences. Emad Bahashwan and Mohja Alshehri

The Open Dermatology Journal

Almohanna HM, Ahmed AA, Griggs JW, Tosti A. Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Alopecia Areata: A Review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020 Nov;20(1):S45-S49. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.002. PMID: 33099384.

El Taieb MA, Ibrahim H, Nada EA, Seif Al-Din M. Platelets rich plasma versus minoxidil 5% in treatment of alopecia areata: a trichoscopic evaluation. Dermatol Ther 2017;30:e12437.

Trink A, Sorbellini E, Bezzola P, Rodella L, Rezzani R, Ramot Y, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, half-head study to evaluate the effects of platelet-rich plasma on alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:690e4.

Bellocchi C., Carandina A., Montinaro B., Targetti E., Furlan L., Rodrigues G.D. The interplay between autonomic nervous system and inflammation across systemic autoimmune diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:2449. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052449.

Song H., Fang F., Tomasson G., Arnberg F.K., Mataix-Cols D., Fernández de la Cruz L. Association of stress-related disorders with subsequent autoimmune disease. JAMA. 2018;319:2388–2400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7028

National Alopecia Areata Foundation: https://www.naaf.org/